Interview with Fox Henry Frazier on 'Weeping in the Tropical Moonlit Night Because Nobody's Told Her'

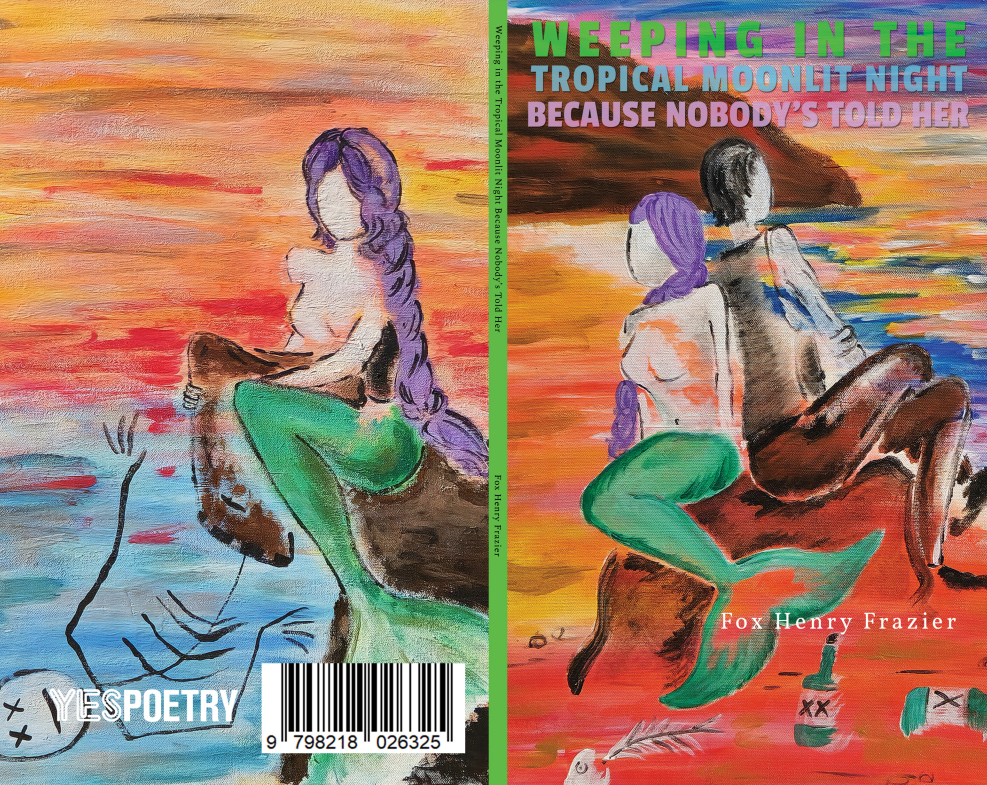

Fox Henry Frazier’s latest book Weeping in the Tropical Moonlit Night Because Nobody's Told Her, which was illustrated by Frazier, Cee Martinez, and Joanna C. Valente, just came out from YP (which you can order here).

Below is an interview with Frazier about the collection and how it came to be.

First of all, why mermaids? (Obviously I love mermaids, but I'm curious what the significance is for you, especially for this collection.)

Well, I wrote this when I had a fever 103°—and that’s not a bad Sylvia Plath joke, I had COVID-19. At one point, early on, regular fever-reducer meds weren’t working, so I had to take a cool bath to try to bring down the fever. And while I was running the bath, I received a—let’s call it a surprising correspondence, I guess—from someone I cared about. The person who sent it knew I was sick, and we hadn’t had an argument or anything; but they sent me a communication that, in the state I was in, felt like sort of a blindsiding barrage of hurtful statements.

It sort of felt like I wasn’t even a person to them; I didn’t get the chance to really say anything, and even when I eventually tried to respond, I was so sick that I barely knew what to say. My experience of being on the receiving end of that was painful and completely unexpected, and I wasn’t in much of a state to process it. So I started to cry.

I was immersed in cool water, and I pulled myself down below the surface of the bath. I remember I had the emotional sensation of retreating from the surfaces of myself—you know, withdrawing into myself, into my own depths. And I remember the physical sensation of crying underwater. And, of course, humans can't really cry under water for more than a few moments, because we can't breathe under water. But sirens can. And then I was suddenly inside this consciousness of a mermaid who was crying underwater because she’s been poured back into the sea; and I knew that she’d turned herself into a betta fish to be close to a human. That was the backstory for why she was crying. And within the hour, I was writing it down. I still had the fever, though. COVID-19 is a gnarly disease.

I remember, when I was writing, thinking about the multiplicity of separate worlds that all exist within the same world. Mermaids and humans provide a lovely metaphor for that, don’t they? We technically exist in the same world, of course, but not really—the deep sea is practically a universe unto itself. I think that everything below the surface of the ocean, for the mermaid in the book — that was how I felt everything below the surface of my skin. My interior life is, for me, oceanic. I’m afraid of sounding a little precious when I say that [laughs], but I guess if Whitman could write, “I contain multitudes,” then there should be no reason why I can’t reasonably compare my psyche to the deep sea.

How would you say your writing has evolved over the years?

I’ve always been pretty cerebral; I think as I’ve gotten older, I’ve been more willing to experience emotion in the relatively public sphere of my art. I think that probably manifests sometimes as—I’m not sure—maybe poems that feel a bit less cerebral, sometimes—or a bit less pointedly experimental? Perhaps a broader, more complex spectrum of emotions at play?

I can say with certainty that I would never have written a book like this in my twenties. No doubt. My twenty-five-year-old self would probably have been horrified at the mere idea of it. [laughs] I would have found the concept absolutely mortifying.

I was much tougher, then, than I am now — motherhood made me soft, for sure — but I also think I’m stronger now than I was then. I have a sense of endurance now that I didn’t have when I was younger. And a sense of calm that accompanies it. When you’re deeply strong, you don’t necessarily need to be tough all the time. Which is, in a way, part of what the book is about. There’s a certain kind of hard-won, deep strength that is required to keep your heart open by choice.

If there was one thing someone could walk away understanding from this work, what would you want someone to take away from this collection?

I truly believe that love is power. I also believe that softness and beauty are sacred. But boundaries are also really important. You can keep your heart open as a person moving through the world and still not put up with bad behavior. You can be tender with someone and still demand what’s right.

You can remain soft and still refuse to let destructive influences into your life. There are certain really sick energies that you have to starve out, within your orbit. You should always protect yourself and defend yourself, and that includes walking away from anyone who mistreats you. When I talk about softness and love, I don’t mean that anyone should be a doormat. You shouldn’t let another person damage or obliterate your identity and replace it with whatever they want to write into the blank space they’ve created in you. That’s bullshit. Obviously.

I also think that remaining a tender-hearted person in this world requires a lot of stubbornness, not just strength. It makes betrayals and unkindnesses hurt a lot more. But it’s what feels authentic to me. I mean, making that effort feels authentic. [laughs] I’m not gonna pretend like I don’t fuck it up every five minutes. But I really do try to live that way.

The last poem is a bit of a departure for the collection in some ways. Speak to that and generally what this poem represents for you.

When I was 11 I listened to Jagged Little Pill for the first time, and at the end there was that hidden track — she sang it a capella, and it was really wounded and tender — and that track then led into a second version of “You Oughta Know,” and it completely changed the entire context of the song for me. I remember sitting on the floor in my bedroom, hoping my mom wouldn’t get home because I didn’t want to have to turn it off (I was a latchkey kid, and I was also definitely not allowed to listen to Alanis Morrissette). It was pretty close to a spiritual experience — my mind was completely blown by the way the hidden track changed the entire album for me. So the last five pages or so in the book are sort of like that, I think.

We know from the earlier poems in the book that this mermaid is in love with someone who is incapable of reciprocating — someone who says tender or sweet things to her, but who ultimately is a bit of a mess. Is withholding, withdrawn—someone who doesn’t appear to want attachment, even if he says he does. She says at one point, “I’m not a complete fool, you know. I always knew that you were sad.” So she can kind of see into this person, at least to some degree. The vibe is that perhaps he’s not well; there’s a deep wound there, there’s damage. She maybe can feel what some of it’s about, but she’s also not prying. She’s not hypnotizing him with her siren song so she can look into him. She just wants to love him. And she isn’t really asking anything in return. She just wants to be around him. But it’s not tenable.

Once she’s back in her own world, under the surface of the waters, she’s got her own interiority back, her own life. And as she’s healing and reclaiming herself and her voice, her own song, her power — she’s starting to see everything that’s transpired more as a wild siren would, instead of from the perspective of a beguiled pet. So she thinks, well maybe I can help. She sings prayers and incantations for this wounded person—into his vibration, as she puts it. (He did, at one point, ask her to bewitch him, after all.) But her energies go to no good end; her attempts aren’t rebuffed, exactly, but she can’t seem to make anything stick in that vibration. So she asks a healer for help. The healer makes an attempt to enter into that vibration, but immediately becomes violently ill and tells her in no uncertain terms to stay away—this energy is no good. And the mermaid starts to realize that you can’t help someone who doesn’t want it.

And that’s generally how mermaids—in my own mythology—tend to see humans. They share some ancestry with us, after all—they’re partly human. They want to love us. They want to help us heal from all the fucked-up trauma we’ve inflicted on the world, and on each other, and on ourselves. But as the human race, we don’t really want to change. We keep making the same unhealthy choices. We keep destroying everything we touch.

And so I pulled in some Eliot, there, at the end — you know, I was thinking of this book as essentially the anti-Prufrock—it really is a love song, and it’s not so afraid of women and bodies; it’s feminine and it’s soft, and it’s from the perspective of a mermaid, not a human beguiled by one. But I was also thinking about how I felt the first time I read the ending of Prufrock, and there was something oddly sad and vulnerable to me about it, too. I mean, Prufrock would rather be at the bottom of the ocean, beguiled and hypnotized, and he thinks he'd feel more at home and less alienated in that strange space. It’s human voices that would snap him out of his mesmerized trance—that would break the spell, causing him to drown. And I was thinking that the mermaid would probably think that’s about right. As our human noise gets louder and louder on this planet, we’re sinking ourselves, no?

She can see that this man—like many humans, maybe even most—isn’t listening to the divinity within himself. He’s leaning more and more into his human noise. And the more it’s all he can hear, it’s inevitable that his sickness will overtake him. It’s sad, on the level of one mermaid talking to her beloved who’s already lost to her—but it’s also meant to set the foundation for my next book. The narrative arc of this forthcoming book is essentially that mermaids have decided humans are an invasive species. They think the only way to save the planet is to bring about the human apocalypse. So they start trying to kill us all. And they’re right, really — this planet is devastatingly beautiful, and it would be better off without us. We’re going to kill it completely if no one stops us. So, yeah [laughs] my next book is gonna be a lighthearted beach read, for sure.

What is something you want to explore more in your art in general?

I struggled with this question to an almost embarrassing degree. [laughs] I think I’ll just describe my current projects and leave it at that.

Let Me Wring Your Heart: Love/Hate Poems for the Vulnerable Troubled Genius Boy — a collection of poems that interrogates the identity of the VTGB, who, as I’ve identified him, is the unsung counterpart to the Manic Pixie Dream Girl in 1990s U.S. cinema. What makes him attractive, what makes him dangerous. What makes him desirable, what makes him toxic.

A Terrible Beauty Is Born — a collection of essays about violence, family, love, death, and radical tenderness.

Alive in Every Version of the Story — a book of eco-poetry about mermaids who declare themselves arbiters of the human apocalypse in order to save the planet.

The Screening — a surrealistic horror novel about a woman who gets broken up with via pre-recorded video and decides to turn it into an art film and screen it at a local gallery. Lightning strikes (literally), and she’s transported to some very strange places.

They Will Never Find All the Pieces — a book about a robot that’s been engineered to be impregnated and give birth. She decides to take her baby and run. (I started this right before the first season of Westworld dropped; I haven’t come back to it since, for fear of overlap. I also haven’t watched any subsequent seasons of Westworld, so I don’t really know how much risk of overlap there is at this point.)

Children of the Stars — a book of epistolary poems in collaboration with Joanna C. Valente, about androgyny and non-binary gender identities.

Gangster Blood & Final Girls — a collection of prose poems/flash essays and visual art in collaboration with Cee Martinez, about serial killers & the victims who survived (and some who didn’t survive) them.

You wear many hats as an editor, writer, and visual artist. Is there a medium that speaks to you the most and why?

I wish I had a sexier answer, but the truth is that poetry is probably most inextricably bound up with my identity. I think everything I do that’s creative is important to me, of course; I'd lose my mind if I couldn't make things. When I took a break from art and writing and editing for a couple years, I had three or four large, pretty lavish gardens that I grew from seed, and I was also designing and sewing a lot. I also built and painted a lot of miniature altars, and sold them. So even when I wasn’t ‘being creative,’ I was definitely still being creative. It was about the only thing that brought me peace, during those years, other than spending time with my daughter.

But when I’ve been preoccupied with other things in life and have decided to step back from writing, I find poems vibrating through me anyway. I mean, they come out in my dreams if nowhere else. So it’s probably always poetry that wins out, in the end.

What are some inspirations for you right now?

Spending time in nature with my daughter and my dogs. Reading a lot. Listening to music. Film. I’d really love to go to a concert, again. As I write this, I’m waiting for my daughter’s third vaccination appointment, to complete her COVID-19 vaxx regimen. I can’t wait to go to a concert; I can’t wait to travel again. I miss New Orleans and New York, in particular, something fierce. In the meantime, spending time at the beach—with beloved friends, and without—is probably the best I’ve felt in the past few years, and where I can hear myself the best. There’s nothing like swimming in the ocean to take you back into yourself, into the purest parts of yourself.

You can order the book here: